Abandonware "After Dark"—How Fair Use Powers Media Studies

A Fair Use Week Guest Post by UVA Media Studies Prof. Kevin Driscoll

Fair use is essential to my everyday work. As a professor of media studies, I depend on the ability to clip, cut, quote, archive, analyze, and compare cultural materials protected by copyright. And, in most cases, I never think about copyright. Thanks to the right of fair use, I can focus on my research and teaching without ever stopping to ask permission of a rights holder or worrying about whether I am going to be sued.

For this year’s Fair Use Week, I would like to reflect on the implications of fair use for a different sort of cultural material: software.

After Dark for Windows, Berkeley Systems, 1989. Source: Computer History Museum, https://www.computerhistory.org/revolution/personal-computers/17/405/1212.

In my Computational Media course at UVA, students learn to think critically about the place of software in society through a series of hands-on programming challenges. We use a wonderful open access textbook titled Aesthetic Programming by Winnie Soon and Geoff Cox (Open Humanities Press, 2020) and the free and open source JavaScript library, p5.js, created by Lauren Lee McCarthy and currently lead by Qianqian Ye.

One of my favorite challenges is to re-create the famous “flying toasters” animation from the After Dark screensaver collection.

After Dark was originally created by two programmers, Jack Eastman and Patrick Beard, and published for the Apple Macintosh by Berkeley Systems, Inc. in 1989. Three years later, they released version 2.0 featuring the flying toasters alongside more than three dozen other “modules” such as a virtual fish tank and fractal generator. Since then, the intellectual property rights to After Dark have been bought and sold so many times that I could not easily identify their current owner.

At a time when relatively few people owned a computer, After Dark was a huge hit. The flying toaster became an icon of the ’90s—evidenced now by countless nostalgic blog posts, YouTube compilations, and kitschy crafts on Etsy. Yet, its creation was more or less an accident. In an interview from 2007, Eastman recalled staying up late to write code while his partner was working the night shift. As he wandered through the empty house, he spotted the toaster sitting on the kitchen counter: “My sleep-deprived brain put wings on it.”

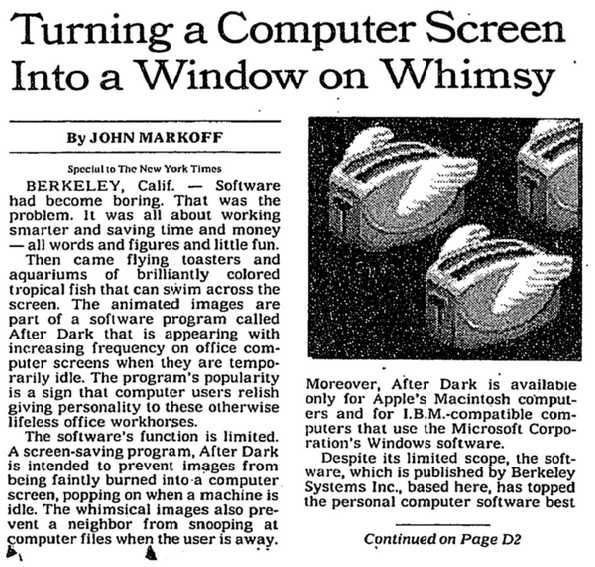

Clipping of the “flying toasters” from After Dark version 2.0 for Macintosh. Source: Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/AfterDark_mac.

As a programming exercise, re-creating the flying toasters requires students to work with fundamental procedural concepts like randomization, repetition, and modularity. They must figure out how to make toasters and toast appear spontaneously in the top-right corner of the screen and fly at different speeds down toward the bottom-left. They may try to recreate the lo-fi sound effects or recreate the rounded corners of the classic Macintosh display.

On a conceptual level, however, this project pushes students to reflect on the material and cultural histories of personal computing. After all, playing around with After Dark raises some compelling questions—beginning with the very existence of the program itself. What was it for?

The term “screen saver” suggests that the flying toasters were intended to prevent “burn-in” on the cathode ray tubes used in computer monitors of the period. Indeed, if a static image remained on the display for too long, a faint shadow would be left behind. Screen savers promised to mitigate the risk of burn-in by keeping the pixels moving around on the screen when your PC was left idle.

Beyond this instrumental purpose, however, students begin to question the aesthetic value and symbolic meaning of the flying toaster. What might this surreal image tell us about computing culture of the period? In what sort of workplace would this humor have been welcome? Was it the digital equivalent of a silly coffee cup or a Far Side calendar?

To answer these questions, we might look beyond the software to the digital archives of techie periodicals like PC Magazine, daily newspapers, or the business press. After Dark seemed to strike a nerve at just the moment when personal computing was becoming mainstream. New York Times writer John Markoff lauded After Dark for its “whimsy” in the face of increasingly “boring” software, and quoted an industry insider who described it as “software that speaks to the heart and the imagination.”

Markoff, John. “Turning a Computer Screen Into a Window on Whimsy.” The New York Times, October 16, 1992, sec. Business. https://www.nytimes.com/1992/10/16/business/turning-a-computer-screen-into-a-window-on-whimsy.html.

The After Dark exercise is one of my favorites because it bridges the social and technical dimensions of media studies. Students journey from the manipulation of pixels and code to the cultural significance of a computer program that works only when you don’t.

And yet, this project is only possible thanks to the robust protections of fair use. At every step in the process, we are pulling copyrighted material off the internet and into the classroom for analysis, exploration, and critique.

The social study of software pushes on the conventional boundaries of fair use. Due to the nature of running code, we could not take a “portion” of After Dark without the whole thing breaking down. Nor would a screenshot or video recording be an adequate substitute for the interactive program.

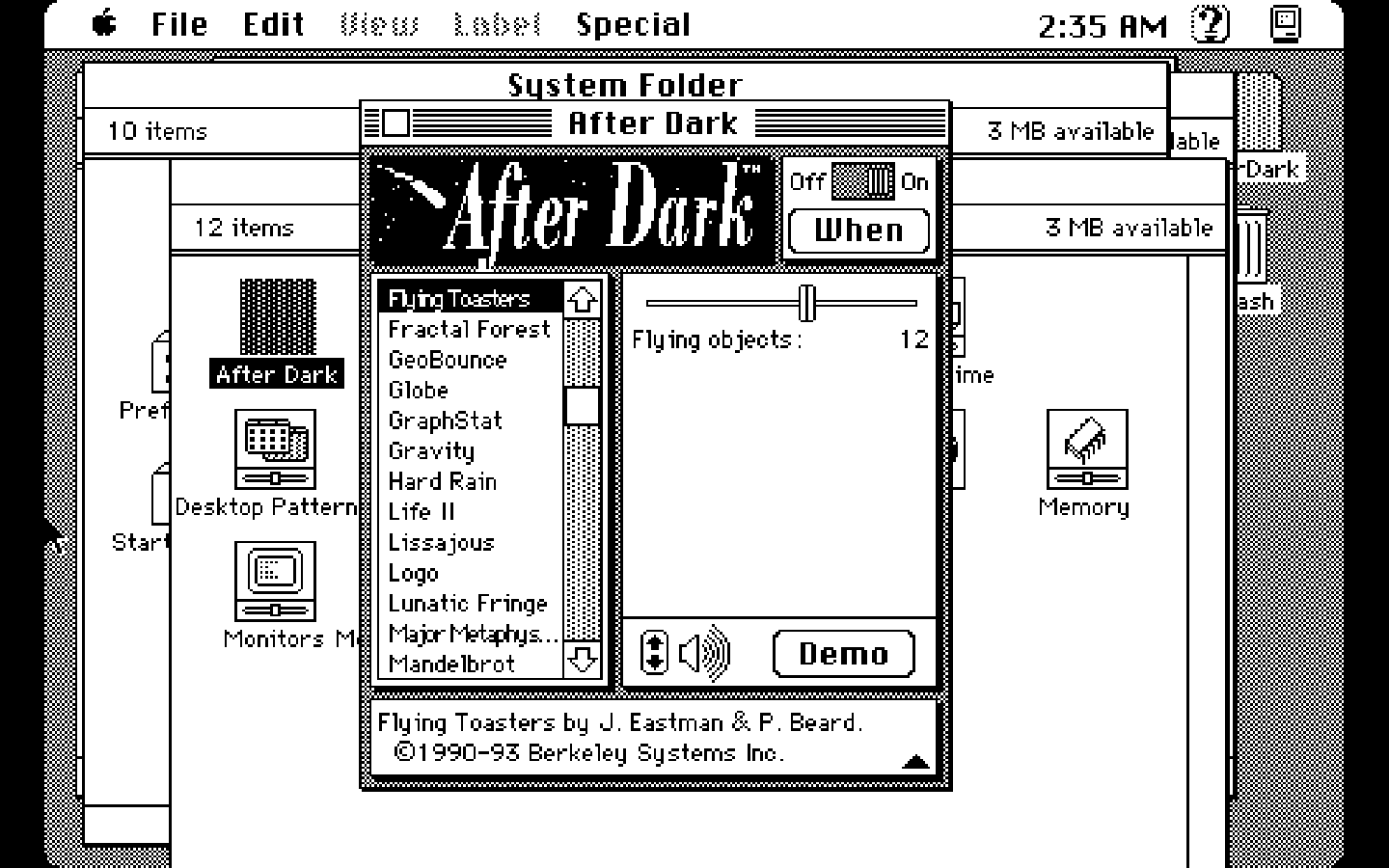

Further complicating the situation, software programs are inextricably linked to their environments. We cannot run After Dark version 2.0 without also running the Apple Macintosh System Software 7.5.3 Revision 2. And since we don’t have access to old Macintosh computers in the classroom, we run After Dark in a web-based Mac emulator on the Internet Archive. It’s copyrighted software (and turtles) all the way down.

Screenshot of the After Dark control panel and copyright notice. Source: Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/AfterDark_mac.

Over the past two decades, software has become the medium for everyday life. As our cultural heritage is increasingly encoded in streams of digital information, accessible only with the help of copyright-protected programs, I find that the need to protect fair use in software has never been stronger.

It is not enough that our right to make critical and pedagogical use of digital materials be codified in law. We also need safeguards against automated systems that would prevent us from exercising our right to fair use.

For the moment, I am encouraged by the After Dark exercise. It is a highlight of the course, and a glimpse of what critical software studies could look like in the future. But every semester, I worry that some piece of the required machinery will go missing, lost to the overzealous protection of copyright.

This is an exciting period of opportunity. Either we will be pushed to piracy and the work will become harder, riskier, and require more arcane knowledge. Or, with the help of far-reaching fair use rights, we will continue to build libraries and archives that allow hands-on exploration of our shared digital pasts, accessible to students, researchers, and the public with winged toasters for everyone.