Publishing, P&T, and Equity, an Open Access Week Miniseries, Part 3: How Librarians Became Experts on Publishing and Equity

Happy Open Access Week! This is the final installment in our 3-part mini-series of blog posts on Publishing, P&T, and Equity. The overarching issue: how to reform our research evaluation processes to eliminate bias and promote structural equity. On Monday I argued for ending P&T standards that reward journal ‘prestige.’ On Wednesday I wrote about why institutions who want to build structural equity should reward open publishing practices in their research evaluation processes. Today I will conclude with a little meta-piece on the Library’s place in all this.

If you made it this far, you may indeed be wondering, why are folks in the library so interested in this issue? And, why should you trust us when we tell you it’s a problem? Well, I’ve got several answers for you.

Library budget crises were an early warning sign about values misalignment between vendors and the academy

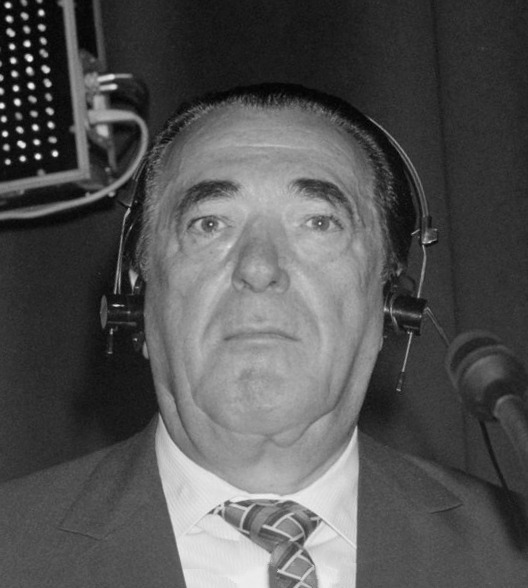

The commercial scholarly publishing business is first and foremost a business, and vendors have prioritized their bottom lines over the values of the academy for decades. We can look as far back as the origins of the modern scholarly publishing enterprise and its arguable founder, Robert Maxwell (father of Ghislaine Maxwell, after whom he named his “superyacht,” the Lady Ghislaine), to see how commercial vendors have been misaligned with universities and libraries. As the Guardian explains, in perhaps the most compelling account of the dysfunction in our scholarly publishing system:

Maxwell’s success was built on an insight into the nature of scientific journals that would take others years to understand and replicate…. Scientific articles are about unique discoveries: one article cannot substitute for another. If a serious new journal appeared, scientists would simply request that their university library subscribe to that one as well. If Maxwell was creating three times as many journals as his competition, he would make three times more money.

unknown photographer (Anefo), CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

This was all fine and good in the go-go days of post-war (and Cold War) government subsidies to research and research institutions, but a business model designed to metastasize until it absorbs every available resource will, sooner or later, cause the system in which it lives to fail. Sure enough, even before the dawning of Big Deals and electronic journal mega-packages, libraries were worried about the explosive growth in journal costs, and the concomitant squeeze on books and all other resources. We called it the serials crisis. Ann Okerson and Kendon Stubbs wrote this warning in 1991:

The continuing serials crisis signals that the present system of scholarly publishing is in danger. Information overproduction, “publish or perish” philosophy, the weakening U.S. dollar, skyrocketing prices and the increasing unaffordability of published research findings–which are, after all, initially produced at universities and often publicly funded–all lead [the Association of Research Libraries] to believe that cancellation projects must be a way-station to longer-range solutions.

Alongside the unsustainable growth in price, the vendors’ quest for profit has fueled a remarkable consolidation in the publishing market. There is now an oligopoly in academic publishing, with a handful of big commercial vendors controlling the majority of the literature in most subjects. This is predictable, rational behavior for a business interested in maximizing profits. But if you have other interests, this mania for mergers and acquisitions (and for colonizing the entire research workflow) can take on a sinister aspect.

So one reason to listen to libraries when we warn you about commercial publishers is that we are the canaries in the coal mine of scholarly communication. We have understood for decades something that most academics still don’t see because of where they are located in the ecosystem: the big journal vendors are consummate capitalists driven by profit first and foremost, and they will use their monopolies to extract resources from universities, even at the expense of scholarly values, and that of course includes equity and justice just as much as access and affordability.

Librarians are experts on scholarly communication, and on fairness and equity in information production and use

Librarianship (“information science”) is a scholarly field, and understanding how information is created, sold, cited, and otherwise used is very much a part of what scholar librarians study and write about. The growing fields of bibliometrics and scientometrics are very much in the librarians’ collective wheelhouse. Librarians were studying publication patterns, citation, publishing business models, and more long before the passion for data and metrics about scholarship captured the broader scholarly community’s collective imagination.

Librarians also have a deep and long-running engagement with the ethical questions that are raised by systems of collecting, organizing, and sharing information. The library community’s interest in measuring and understanding information has always been informed (and, increasingly, throttled) by questions of justice and equity.

Libraries have tried for decades to change the system, and we’ve learned fundamental change will require changing scholarly incentives

That 1991 essay on the “serials doomsday machine” describes a series of initiatives that research libraries should launch to counteract the armageddon unleashed by Robert Maxwell’s commercial scholarly publishing machine. To libraries’ credit, we did those things! Libraries created SPARC, launched open institutional repositories, and took a dozen other steps to try to turn back the tide of the serials crisis. The results were mixed, for sure, but I don’t think anyone can say libraries haven’t been working, all these years, to fix the broken system.

Our core mission remains ensuring our own scholars have access to what they need to do their research. As long as scholars have an incentive to publish with the “prestige” outlets, we will be forced to reckon with the vendors to acquire a significant portion of the research our campuses need.

So, as we all work toward systems that foster structural equity (and to dismantle systems that create and amplify injustice), institutions could learn a little bit from libraries. We’ve been on the losing end of this broken system for decades, and it gives a perspective that our colleagues and partners around campus might find valuable.