Thanks to fair use, podcasting about dancing is easier than dancing about architecture

A Fair Use Week Guest Post by Prof. Katie Schetlick, UVA Drama Dept.

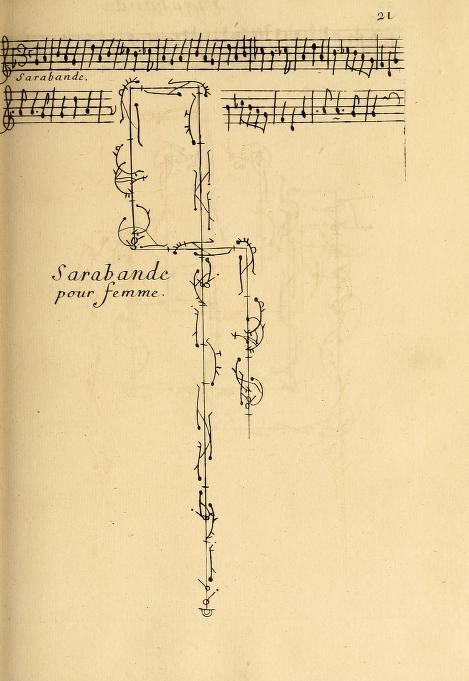

In my course How Dance Matters we explore the conundrum of attempting to capture, to hold still dance. We begin with the question of the archive, particularly how the archive reveals the matter (material) historically considered to constitute “the dance.” In three words: what matter matters? We soon learn, through a study of early 18th century dance notation developed in France under the auspices of King Louis XIV, that dance in a western historical context becomes defined by what can be accounted for, and in Beauchamp-Feuillet notation that was the path of the dancer through space, the intricate movement of the feet, and simple hand motions. That was the dance, period. Nothing was considered to be unaccounted for. There was no sense of lack. With a codified notation system that the King divined as THE system of “making dance legible on paper,” came the ability to author dance, quite literally to write dances, to become a choreographer. Dance masters with the knowledge of the notation system quickly took to inscribing their name at the top of the inked steps they reconfigured.

My students, born well after the advent of personal video cameras, of course quickly recognize the shortcomings of this 18th century system for our contemporary notions of choreographed dance. What about the torso? The head? The pelvis? The uniqueness of each dancing body? It becomes clear to them that the ontology or beingness of dance and even notions of corporeality itself are historically and culturally specific. The immediate assumption, however, is that our current technology makes up for any previous lack. But then comes the question, “Is a video recording of a dance a wholly accurate and complete archive of the dance work?”

Over the course of the semester, we continue to think critically about notions of the archive and authorship through the process of making a podcast. Each student works to script a podcast episode about a choreographer that has visited UVA during the first fifteen years of the UVA Dance Program (2006-2021). While a podcast might seem like a curious medium to explore such a visual art form, the digital audio format offers new modes of criticism and expands the archive beyond the visual to include all potential audiences. In addition to a vivid audio description of the dance itself, the episodes explore the major themes that emerge in the work performed by the UVA student dancers alongside the choreographer’s biography and their unique contributions to the field.

After my first semester implementing the podcast project, I wondered how the episodes might be more dynamic and serve as a richer archive if audio clips of the choreographer’s voice and the music from the performance were included. Because I was hoping these student crafted episodes would actually become part of the dance program’s archive – that they would actually exist in the world and be made available to the public – I got nervous about issues of copyright infringement and sought advice from a team of UVA librarians. That’s when I met Brandon Butler.

In our first meeting, Brandon simply smiled and said two words, “fair use.”

After first learning that “fair use” functions as the balancing force between copyright law and the First Amendment and then taking a deeper dive into Brandon’s recommended source, “Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use” published by the Center for Media and Social Impact, I realized that my students actually had a lot of leeway to thoughtfully include short clips without having to ask permission or pay a fee. Not only would “fair use” strengthen the composition and liveliness of their episodes, but it would also provide them with some guiding principles for effective dance scholarship and dance creation and bring us back to our critical conversations about the archive and authorship in dance.

Following a fair use workshop facilitated by Brandon, my students knew to ask themselves if the extracted sound clip was being used for a new purpose, in a new context, or as evidence to support an argument. The choreographer’s voice couldn’t simply be inserted as a substitute for their own analysis nor could they play the clip without contextualizing what the listener was about to hear. They also had to consider how much of the selection was appropriate to use given the purpose of its inclusion and the length of the original material. Having to practice “fair use” for their public facing podcasts episodes, students also learned important skills for when and how to include sources in their written essays and started to ask more critical questions about the dissemination of dance on social media and in the global economy.

Thanks to the practice and teachings of fair use, the UVA Dance Program will have a more robust public archive of its first 15 years producing dance concerts.

Here are two episodes from the podcast Hoo’s Got Moves: